Fish Food: Episode 622

The Lindy Effect and the optimisation trap, 'good enough' prompting, SEO for LLMs, AI poetry, and listening to forests around the world

This week’s provocation: The Lindy Effect, and the optimisation trap

A while back I read Shaw Talebi’s reflections from doing Nassim Taleb’s Real World Risk Institute course. One of the concepts featured in the course is The Lindy Effect - a principle derived from the observation that the future life expectancy of non-perishable entities, such as technologies, ideas, or institutions, is proportional to their current age. Put simply, the longer something has lasted, the longer it is likely to endure (sidenote: the concept was named after a New York deli and originally referenced the career prospects of comedians).

The Lindy Effect and corporate longevity

When we apply this idea to corporations, the Lindy Effect suggests that older companies have proven their resilience to market fluctuations, competitive pressures, and shifting consumer demands, which in turn increases their odds of future survival. And studies have indeed shown this to be true. The chart below (source) shows the survival rate over time of businesses that were established in 1994 right up until 2023. 20% of businesses had closed down within a year, 50% after five years and so on. The fact that this is a curve rather than a linear decline is the Lindy Effect - the older a business gets the higher its marginal survival percentages get.

Yet the Lindy Effect does not guarantee longevity. Instead it also highlights a key dichotomy: while enduring companies benefit from established brand equity, institutional knowledge, and operational stability, they are also at risk of becoming complacent, resistant to change, or vulnerable to disruption by more agile competitors.

A comprehensive study by the Telfer School of Management at the University of Ottawa into the implosion of Canadian Telecoms giant Nortel (the once market-leading company filed for bankruptcy in 2009) tells us a lot about how this can happen. The study's lead author, Jonathan Calof, said:

‘There were three major factors that caused the failure. When Nortel was a market leader in the ’70s, it developed an arrogant culture, which led to poor financial discipline. Then in the ’90s, it focused so intensely on growth that it broke its ability to innovate and read the market. And after the tech bubble popped, it turned inward and cut costs to the point where it alienated customers.’

Arrogance, pursuing growth at all costs, turning inwards, efficiency at the expense of innovation. It’s a familiar story.

The Optimisation Trap

There are, let’s not forget, huge benefits that can come from continuous incremental improvement but there are also limits to the gains that can be secured by optimising an existing system. Sometimes we need to think bigger and redesign the system itself in order to take a leap forwards. And this is where problems can arise.

Optimisation, by its nature, reinforces the current way of doing things. It focuses on extracting maximum value from existing systems, products, or processes, often at the expense of exploring new paradigms. While this can enhance operational efficiency, it also narrows an organisation’s focus, creating blind spots to disruptive opportunities and external threats. Over time, the more optimised a company becomes around its existing model, the harder it becomes to envision, let alone embrace, transformative change.

We might call this the ‘optimisation trap’ - a relentless focus on improving existing advantages combined with a hubris that results in an unwillingness to think differently, leading to diminishing returns and a dangerous myopia that stifles innovation and long-term growth. There’s several signs of this happening:

Cognitive Inertia: As teams and leadership become deeply familiar with optimised systems, their thinking aligns more tightly with existing paradigms. This creates a bias toward incremental improvements over bold, untested ideas.

Resource Allocation: Optimisation often demands significant resources—time, talent, and capital—leaving little bandwidth for exploratory or disruptive initiatives.

Cultural Resistance: Organisations optimised for one model often develop cultures that reward stability and predictability. This can result in skepticism or outright resistance to disruptive ideas that challenge the status quo.

Success Reinforcement: Ironically, success exacerbates the problem. The more an optimized model delivers results, the harder it is to justify deviating from it. This creates a feedback loop that makes transformative thinking feel unnecessary or excessively risky.

I’ve written before about how companies can break out of optimisation. But today I want to leave you with one thought on this.

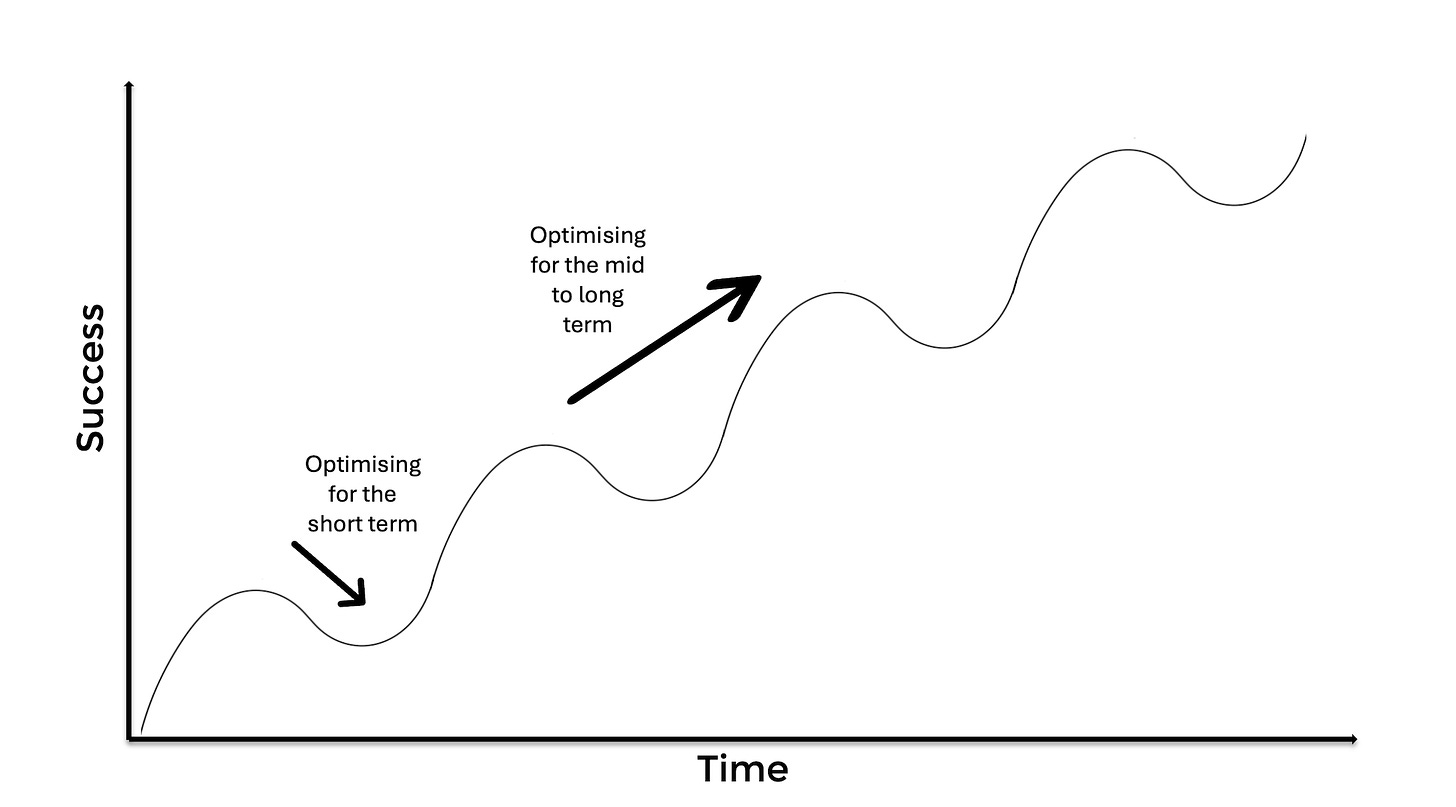

One aspect of the optimisation trap is that we optimise for the wrong timescale. And this can apply to people as well as organisations. Graham Weaver phrases this well in this short Reel. As we progress through life, working to make our situation better, sometimes we will be unwilling to make a bigger change because of the short term challenges that this brings. In other words, as the chart below shows, we go down before we go up.

Graham’s point is that we’re often continuously optimising for the short term, and are therefore unlikely to do anything that will put us in a worse situation, even if that is temporary. So we don’t make the move. But, in our personal lives, as in business, this can mean we end up climbing the wrong hill. Optimising on a longer timescale however, means that we recognise that short term challenges can lead to long term benefits and progress. It frees us up to make bigger, more breakthrough decisions and changes. And it helps us to get out of the optimisation trap.

Image: Shaw Talebi. Data source: BLS.

If you do one thing this week…

I really liked Ethan Mollick’s thoughts this week about ‘good enough’ prompting for AI tools. He references a study of Doctors using GenAI tools which revealed some interesting observations around algorithmic aversion (our hesitancy to take advice from machines when they conflict with our judgement, even when the machine may have a higher degree of accuracy) and also how the Doctors were using the AI more as a search engine and consequently struggling to get the value out of it.

This, notes Ethan, is a common problem and the answer is not necessarily to learn complex ‘prompt engineering’. Framing it as a complicated learning task will simply discourage people from trying to understand how to work with AI and anyway, there is no clear science yet on how to do this (‘researchers are still arguing over the most basic foundations of good prompting. This is because AIs are inconsistent and weird, and often have different results across different models’). The need to know how to do complex prompting may be less of an issue over time anyway - AI’s are getting less sensitive to nuances in prompts, but also better at interpreting intention, and there are tools that can help (I like this prompt generator from Anthropic which Ethan mentions).

He suggests two pathways to get started…good enough prompting for tasks, and good enough prompting for thought. For the former, try it out on lots of different tasks that you do in your day to see how it does. He says to ‘treat the AI like an infinitely patient new coworker who forgets everything you tell them each new conversation’. For example, give it good and bad examples, step-by-step directions, feedback and so on. When it comes to good enough prompting for thinking, you should simply use it as a thinking companion and converse with it using natural dialogue (maybe using the voice-driven interfaces) and not overcomplicate it. I’ve also noticed that politeness gets you better answers, spookily enough. You can use it, says Ethan, as a rubber duck: ‘…the popular idea in computer programming that, if you explain an issue to an inanimate rubber duck on your desk, you will work through the problem on your own by talking it out.’ Useful advice.

Photo by S. Tsuchiya on Unsplash

Links of the week

Here’s a folder filled with 25+ of the latest 2025 trends presentations including ones from Accenture, CB Insights, Contagious, Forrester and Gartner (and it’s free to access). Strategist Amy Daroukakis has used Notebook LM to create a summary podcast which captures the highlights - genius.

‘As some of those people who don’t understand it, rather than pick holes in the new look – we decided to take a look at how we’d have rebranded this icon’. The best hot take on Jaguar, and the only one I’ll mention (HT Tom Goodwin)

Crikey. According to this study AI generated poetry is indistinguishable from human generated poetry, and is rated more favourably (HT Pete Marcus)

This was a useful post by Crystal Carter (Head of SEO at Wix) on SEO for brand visibility in LLMs (HT Michelle Goodall)

Several news outlets (including The Guardian) have reported seeing much higher traffic (proportionate to followers and in total) from Bluesky than Threads and X. Journalist Anne Applebaum said this week that the latter two are ‘now specifically engineered to downgrade, hide, suppress real journalism’, and Bluesky have confirmed that they don’t de-promote links, unlike other platforms. Looks like Bluesky is the place to go to share interesting links then.

This week I wrote something for Think with Google collecting some key themes and some of my key highlights from the past year of Google Firestarters episodes

Some wise words from Zoe Scaman on making the leap to do your own thing. If you’d like to read some advice from me on the same topic, this is something I wrote a few years back

Quote of the week

‘One day, in retrospect, the years of struggle will strike you as the most beautiful’.

Sigmund Freud, in a 1907 letter to Carl Jung.

And finally…

‘Tune Into Forests From Around The World. Escape, Relax & Preserve’. Tree FM is an amazing idea. (HT Swissmiss)

Weeknotes

This week I was back workshopping here in the Middle East. It’s a pretty full on trip (2 weeks with 9 days workshopping and then a keynote at BAM Congress in Brussels) so next week features more #awaitinganaudience.

Thanks for subscribing to and reading Only Dead Fish. It means a lot. If you liked this episode please do like, share and pass it on.

If you’d like more from me my blog is over here and my personal site is here, and do get in touch if you’d like me to give a talk to your team or talk about working together.

My favourite quote captures what I try to do every day, and it’s from renowned Creative Director Paul Arden: ‘Do not covet your ideas. Give away all you know, and more will come back to you’.