Fish Food: Episode 645 - How streaming has changed music

Spotify's effect on music and creative process, AI eats the world, AI transformation strategies, and the AI whitecollar 'bloodbath'

This week’s provocation: We shape our tools, and then our tools shape us

Was it Marshall McLuhan (or Winston Churchill or John M Culkin) who said: ‘We shape our tools and thereafter our tools shape us’? After last week’s post on what the end of the silent movie era tells us about inflection points in the creative industry, subscriber Tom Goodwin dropped me a note commenting on how streaming had completely changed the parameters by which TV and Movies are made (length of episode, number of episodes in a season, how episodes are written). It sent me down a whole bunch of new rabbit holes relating to how streaming has changed our relationship to the consumption of music and film.

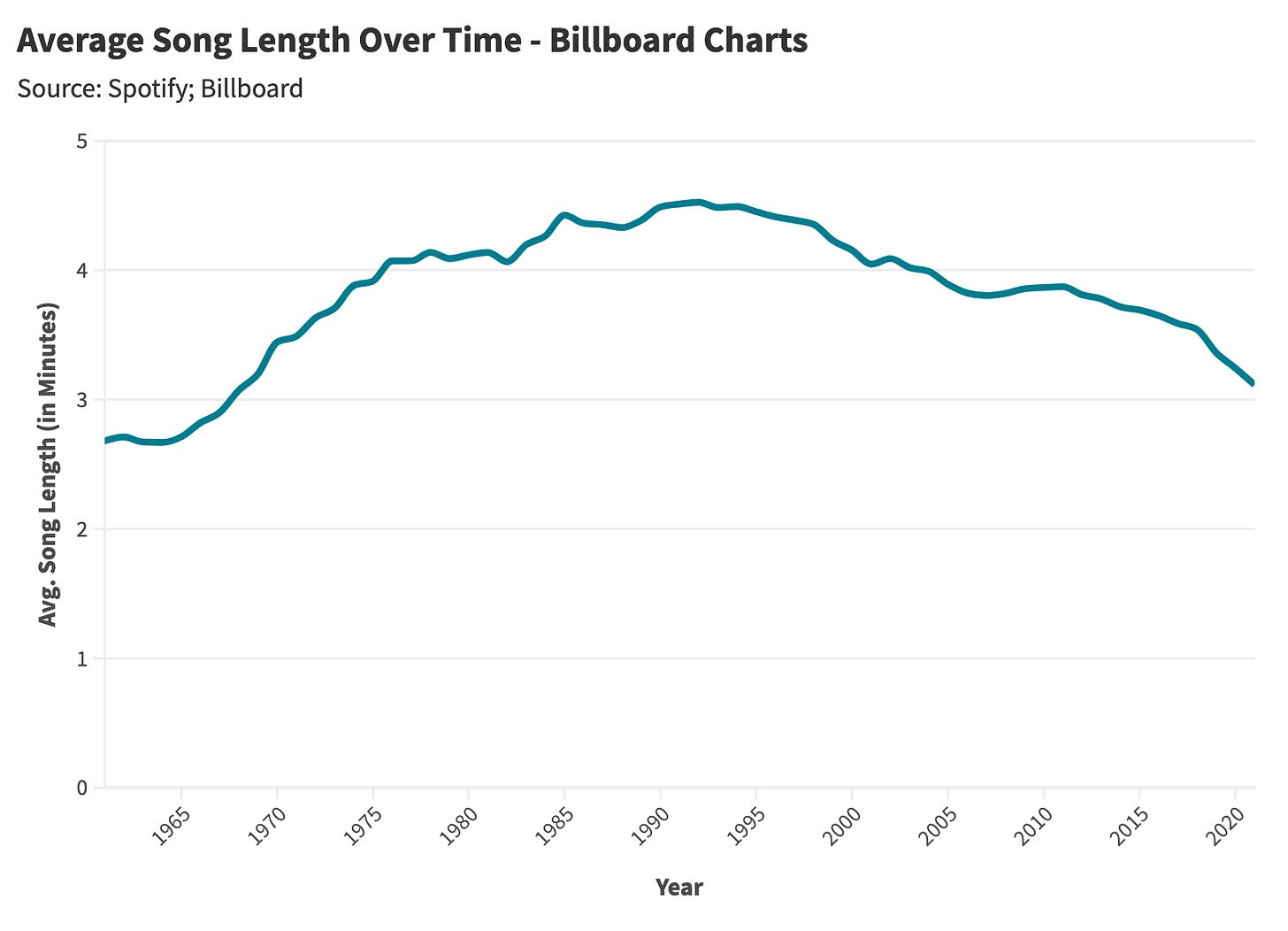

One of the most fascinating examples of this is popular music. Music streaming has impacted music creation in some interesting ways, arguably both good and bad. In his peerless analysis of how music has changed since the 1950s, Daniel Parris notes how the rapid advancement of form factor and storage capacity (vinyl to cassette to CD) led to an increase in average track length with song durations peaking in the mid-1990s. As streaming became more popular, song length begins to decline - a phenomenon which Daniel notes is likely down to the decoupling of songs and albums, and artists focusing on maximising individual tracks rather than cohesive album concepts, and the pay-per-play model which rewards the number of listens rather than total listening time (‘streaming ten 31-second tracks pays more than a single stream of a 310-second song’).

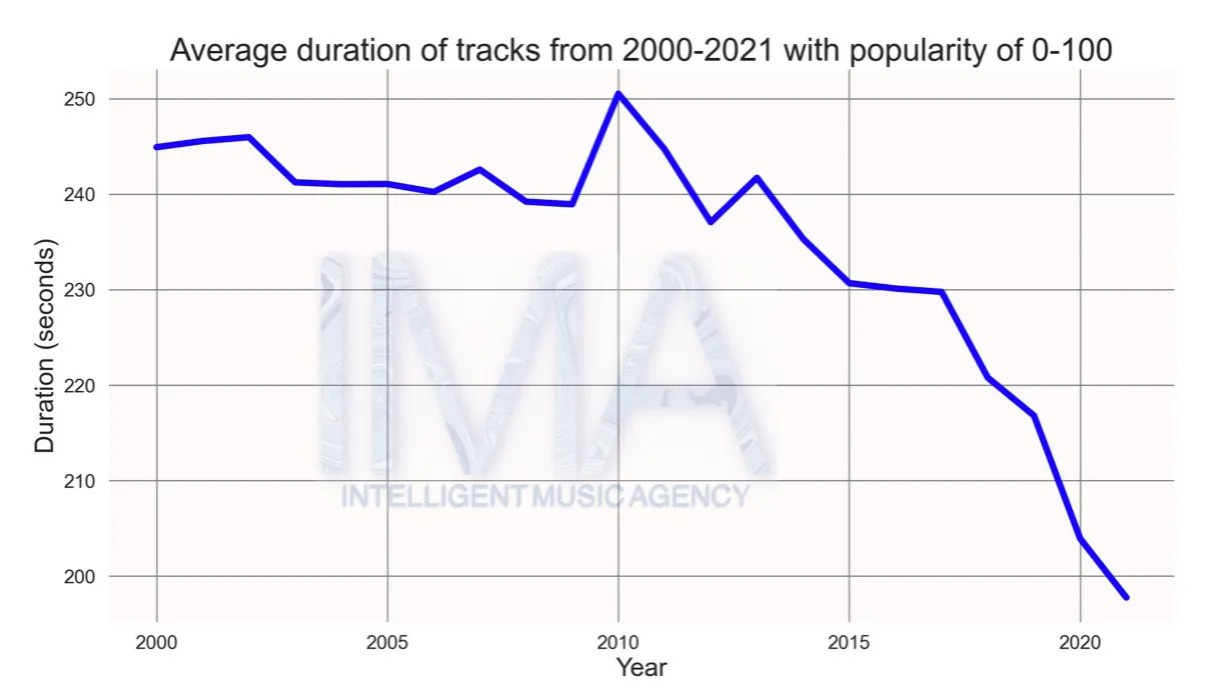

Similarly, researchers Parth Sinha, Pavel Telica and Nikita Jesaibegjans analysed a dataset consisting of 211,000 songs initially released between the years 2000–2021 and also discovered a relatively steep decline in song duration beginning around 2010.

The researchers indexed song popularity against song duration and further discovered that the most popular songs produced and released on Spotify also show a definite trend towards shorter duration.

Daniel Parris notes another trend that has risen alongside streaming. Song tenure (the average weeks in the charts) has declined while the diversity of artists on the charts has increased. In another words more artists make the charts for shorter periods of time. Streaming may have resulted in sharper spikes of popularity for individual tracks, but it also seems to have contributed to greater diversity in listening. An analysis of Spotify data and music charts across 39 countries revealed an upward trend in music consumption diversity that started in 2017 and spans across platforms. This suggests that, rather than homogenising global music tastes, streaming platforms may be facilitating a divergence with different regions embracing a wider array of local and international music. Another longitudinal study found that users exposed to a diverse range of digitally-enabled music recommendations developed greater openness to the genre over time, even if they were initially unfamiliar with it. Of course there may be other factors involved here (like TikTok), but the sheer accessibility of so much diverse music seems to be having an impact. Spotify alone has around 675 million monthly active users, more than 100 million tracks and over 6,000 genres of music (you can see them all here).

Streaming has impacted music composition in interesting ways as well. Spotify’s pay-per-play model means that a song needs to be played for 30 seconds to be considered a stream, incentivising artists to write tracks with shorter intros and more immediate hooks. As an example, this study used a deep learning framework to analyse song structures and found that modern songs often feature choruses and hooks earlier in the track to capture listener interest quickly. It’s perhaps little surprise that tracks are being written with this in mind when research has shown that listeners are more likely to skip songs during less engaging sections, such as extended intros, and that songs with immediate hooks tend to retain listeners longer.

And let’s talk about another significant impact of streaming. The pressure to generate streams and to be included into as many playlists as possible has led to the creation of a whole new type of music, dubbed ‘Spotify-core’. A genre-defying blend of mellow, mid-tempo, lo-fi or acoustic-tinged music, these tracks are engineered for passive listening and for pleasing the algorithm, and designed to blend seamlessly into multiple playlists, to have broad appeal, and to avoid triggering skips (basically any Spotify-compiled and recommended playlist with the word ‘chill’ or ‘vibe’ in the title will be full of it).

Spotify-core requires little effort on behalf of the listener, but serves to provide background for busy, anxious and stressed people whilst they are working or doing other tasks. As John Harris of The Guardian wrote recently, Spotify has no direct involvement in the creation of Spotify-core music but it’s algorithms and models are incentivising a whole production-line of suppliers who are specialising in so-called ‘perfect fit content’. Technology has always reshaped artistic creativity, he writes, but ‘what sets Spotify apart is something much more insidious: it goes beyond alterations of music’s forms into what we think music is there to do’.

According to journalist Liz Pelly, who recently wrote a book on the topic (Mood Machine: The Rise of Spotify and the Costs of the Perfect Playlist), Spotify realised as far back as 2012 that active listening was a much smaller proportion of listening than all the hours that users were clocking up using music as a background experience. This led the company to start promoting playlists as the background to a diverse set of activities including work, fitness, studying and even trying to get to sleep. In doing so they broke down traditional genre boundaries to define and group music by mood and function. But in pushing music as background, and to fit a particular mood, Spotify somehow managed to disrupt a bond which has existed since the dawn of popular music - it detached the music from its maker. As AI generated music offers up a tantalising opportunity for volumes of cheap, playlist-filling content, this phenomenon is unlikely to disappear anytime soon.

A while back I wrote about whether social media algorithms flatten culture, and whether innovation and diversity is stifled when creators are incentivised to produce content that aligns with algorithmic preferences. Where I ended up was to suggest that algorithms in fact play a dual role in both in cultural homogenisation and cultural diversity - they simultaneously encourage certain approaches and a rapid dissemination of global cultural phenomena whilst also providing a platform for cultural diversity and uniqueness.

I suspect the same may be true of streaming - it homogenises at the same time as diversifying. Of course it’s tricky to establish direct causal links when there are other factors that are likely involved, but streaming seems to have had a diversified impact, whether that be on song duration, song structures or even musical genres and the way that we think about music itself.

As we move into an era of far more ubiquitous use of AI tools it will be interesting to see how AI will reshape our expectation and behaviour.

We shape our tools and then our tools shape us.

Rewind and catch up:

AI, and inflection points in the creative industries

Innovating employee experience in the age of AI

If you do one thing this week…

Every year analyst Benedict Evans produces a mega-deck exploring ‘macro and strategic trends in the tech industry’. They’re always very insightful and his new one looks at the development trajectory of AI (of course). Highlights for me included points about how ChatGPT is the currently the only AI ‘brand’, how software is moving from deterministic to probabilistic, and how for most people in most jobs it’s not easy to work out what to do with an LLM. Worth a look through.

Links of the week

IBM have a useful report (PDF) on agentic AI in the organisation. There’s a TL;DR summary here. Interesting nuggets include agentic AI as an operating model, ‘touchless workflows’ (‘by 2027, 85% of execs expect agentic systems to run major parts of operations’), human roles shifting from execution to orchestration, context, creativity and control.

I hadn’t seen this before but last year the UK Govt produced a report looking at the upsides and risks around five different scenarios for the trajectory of advanced AI. These included ‘Unpredictable Advanced AI’, ‘AI Disrupts the Workforce’, ‘AI Wild West’, ‘Advanced AI on a Knife’s Edge’ and ‘AI Disappoints’. There’s some scary risks talked about here but perhaps the most concerning aspect they talk about is the lack of global coordination across all scenarios.

Well, of all the places for this to come from - the US Marines have produced a rather good report (full report here (PDF), summary here) on how to implement AI at scale. I liked the focus on AI as embedded within wider digital transformation rather than treated as something separate, AI fluency training at all levels, governance that enables not blocks, use cases driving strategy, and embedded transformation teams.

Pair that with this J & J case study (WSJ, Greylock, but explained here by Ross Dawson) featuring a divergent-convergent ‘thousand flowers’ strategy which involved seeding over 900 use cases to discover the 10-15% which drove 80% of the value.

Pair that with this short TikTok in which Karl Yeh articulates the 'bottom-up trap' and the 'top-down fantasy' that is going on in AI implementation in many companies right now. The disconnection from the reality of tasks and processes, the lack of training support, the retro-fitting of fancy tools to business challenges, the fear and concerns. It's all there.

Lots about AI and the future of work this week. As the Anthropic CEO talked about a ‘white collar bloodbath’, Bruce Daisley had some sobering thoughts about AI's impact on knowledge work, and Ethan Mollick wrote about the failure of leadership to question assumptions and properly consider how human capability can shift focus

For a more positive spin, British philosopher Andy Clark has an elegant short essay on how GenAI can be an ‘amplifier and transformer of creative human intelligence’

And finally…

Well, if you need some light relief after all that AI talk, here’s an hour and 20 minutes of every single Premier League footballer saying how to pronounce their name.

Weeknotes

This week I began working with an African bank (another bank) on a digital ecommerce and strategy project which will last through June, alongside other stuff. And next week I’ll be speaking about AI transformation in the creative industry at a Moore Kingston Smith event, as well as delivering a virtual version of the IPA Advanced Application of AI in Advertising, which is always fun.

Thanks for subscribing to and reading Only Dead Fish. It means a lot. This newsletter is 100% free to read so if you liked this episode please do like, share and pass it on.

If you’d like more from me my blog is over here and my personal site is here, and do get in touch if you’d like me to give a talk to your team or talk about working together.

My favourite quote captures what I try to do every day, and it’s from renowned Creative Director Paul Arden: ‘Do not covet your ideas. Give away all you know, and more will come back to you’.

And remember - only dead fish go with the flow.

As a "veteran" musician, this topic hits a nerve for me. The provocation that we shape our tools, and then our tools shape us totally resonates. And of course, it shapes us not only at an individual level, but also the whole system. The music industry used to have a lot of constraints (mainly shelf space in record stores and prime radio time), and many gatekeepers - who for better or worse became "tastemakers". The game has flipped on its head and now it is all about navigating the attention economy.

What I'm less sure about is the degree to which the payment model of streaming services is directly influencing the way people write music. I'm might be naive or idealistic, but my personal perspective is that amount that the streaming services pay is such a pittance that there is little point bending the creative process. Of course if you are just creating slop for playlists etc, then that might be a different story. But I cling to the notion that people's whose music actually connects is coming from a more authentic source.

I'm literally in the process of uploading a new album to the digital distribution services and planning its release - my band's first in 8 years, and then 10 years before that (so we've seen a lot of change). The thing that disheartens me is the nowadays the narrative is that the actual album release is the end of the process, and there is a drive to drip feed the songs one by one so as to play to the algorithms and short attention spans. It is what you mention in the article - "artists focusing on maximising individual tracks rather than cohesive album concepts". I know that albums weren't always a thing, but I love the idea of a family of songs that weave a sonic and thematic narrative, and I'm sad to see the digital platforms squashing that.

As a final aside, my band has actually been caught out by another phenomenon related to what we are talking about. While digital music obviously dominates, there is an increased interest and expectation around vinyl. I'm on board with that, and particularly like seeing the artwork in all its glory. Apart from the huge upfront cost of pressing vinyl and then posting it, there are physical constraints to the medium, and it is not advisable for each side to be longer than 22 minutes, and 25 minutes is basically the maximum. Our album clocks in at 51.5 minutes, which creates a conundrum. So I guess this highlights that there is always this dance between our tools and our creative process, even if the form changes.

As always, thanks for your work Neil - always thought provoking!!