Fish Food: Episode 648 - Gigantomania and why big projects go wrong

Why big stuff goes wrong, technology and more free time, cognitive debt, the state of strategy, and think-prompt-think

This week’s provocation: Think slow, act fast

This weeks news about the further delays and overspend costs associated with the UK’s HS2 high-speed rail project had a distinct air of inevitability about it. Government infrastructure initiatives and large corporate projects that don’t overrun and exceed budget are a unique kind of rarity. Oxford academic Bent Flyvbjerg, who co-wrote the excellent ‘How Big Things Get Done‘, compiled a database of 16,000 such initiatives and found that only 8.5% of projects deliver to their original projected cost and time projections, and only 0.5% deliver to initial cost, time and benefit forecasts. Wow.

Institutions, large corporates and big consultancies often seem to have a preference for what you might call ‘gigantomania‘ – centrally-controlled grand projects of significant scale that are often supplemented by a desire to use the latest technology. Western observers in the first half of the 20th Century used the phrase to describe Stalin’s predilection for huge scale industrial and engineering schemes in Soviet Russia. These infrastructure projects (including dams, hydroelectric and irrigation programmes) almost always vastly exceeded their projected time and budget, led to high accident rates, poor quality production, and high environmental impacts.

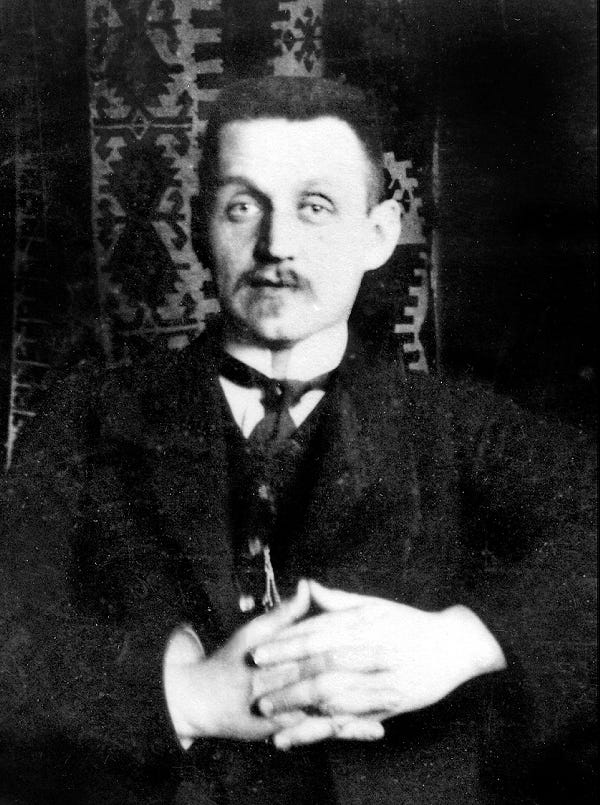

In the early 20th Century Russian engineer Peter Palchinsky was something of an outlier in advocating for a more scientific method within Russian industry. He believed that rather than seeing every problem as a technical one that could be solved using the latest technology, engineers should follow three simple rules for industrial design that would enable greater adaptability whilst mitigating risk:

Variation: Actively seek out and try many different ideas and approaches, rather than committing to a single grand plan from the outset.

Survivability: Experiment with new ideas on a small scale, where potential failures are ‘survivable’ and do not lead to catastrophic consequences for the entire system or population.

Selection: Implement quick and effective feedback loops to learn from both successes and failures. This continuous learning allows for adjustments and improvements as projects progress.

Palchinsky’s principles championed a more iterative, human-centred and adaptive approach to problem-solving and large-scale projects which contrasted sharply with the gigantomania and disregard for human cost that characterised much of early Soviet industrialisation. He emphasised the importance of thorough research, data collection, and realistic assessment before embarking on massive projects. He sought to organise engineers into professional organisations to foster the exchange of ideas and ensure their voices were heard in decision-making. He was against allowing ideological zeal and grandiosity to override sound engineering principles, safety, and economic realities.

Many of today’s organisations can learn a lot from Palchinsky’s thinking. His three principles offer a pretty good set of guidelines for learning fast about the potential value in AI application and yet I’m sure we’ll see more than our fair share of AI gigantomania. In many ways Palchinsky's ideas can be seen as a precursor to modern systems thinking in that he understood that industrial projects were not isolated technical challenges but complex systems intertwined with social, environmental, and political factors. He looked at the broader context and long-term effects of decisions. And AI should be no different.

Yet if we are going to do big stuff we should do it well. I’m going to finish this post by returning to Bent Flyvbjerg and Dan Gardner’s excellent book and five essential conventions that I’ve taken from it that can help avoid the classic errors that often hinder big initiatives:

Don’t climb the wrong hill: Many projects go wrong before they even begin because the problem isn't framed well. The book makes a great case for extended front-end planning and taking time to make sure we’re solving the right problem. Go slow to then go fast.

Planning fallacy should be treated as the rule, not the exception: Optimism bias (believing things will go better than they are likely to) and strategic misrepresentation (intentionally underestimating cost to get approval) are endemic in project planning. Use reference class forecasting (analysing data from similar past projects) rather than internal wishful thinking. Study patterns of failure and success in your domain. Your project is probably less novel than you think.

Scale is a risk multiplier: Big things amplify small errors. A 1% mistake in scope, budget, or sequencing can become a major issue at scale, so it can be useful to break projects into modular, repeatable units where possible. Modularity helps to reduce complexity, enhance predictability, and enable faster delivery.

Right people, right incentives: Misaligned incentives (especially among contractors, political sponsors, or consultants) breeds dysfunction. Many cost overruns stem from human misalignment, not technical issues. Reward systems should prioritise long-term performance over short-term gains. Build in accountability and monitor alignment continuously.

Make the invisible visible: Small problems buried in complexity often sink big projects. Transparency means visualising interdependencies, making assumptions explicit, tracking progress rigorously. While planning should be considered, delivery should be fast and iterative. Producing something tangible quickly can help build momentum. Success often comes from managing perception, not just execution, and so shaping the story is important. Many project failures are political.

The Sydney Opera House was expected to take 4 years and cost $7 million. It famously took 14 years and cost $102 million. The design was approved before technical feasibility was known. Builders were solving basic engineering problems whilst they were actually building. But the equally ambitious Guggenheim Bilbao opened on time and on budget. The difference was meticulous planning, highly-aligned stakeholders, and tight contractual controls with clear incentives.

Successful big projects may be well-executed ones but they’re also better designed from the start.

Rewind and catch up:

Superagency: Amplifying Human Capability with AI

AI, and inflection points in the creative industries

If you do one thing this week…

The promise of new technology has always been that it will free us up to spend time on more interesting or valuable activities but through history this has not generally happened. Data from the OECD shows that the average time spent on leisure has decreased since the 1980s, and now new research from Lloyds Banking Group (PDF) shows that in the UK, the average person has only 23 ‘genuinely free’ hours a week (from a total of 168). Predictions of how AI-driven efficiency will free up time are already widespread, but will this actually mean more ‘free’ time? It’s a big question, and by no means a given. (Guardian opinion piece on the research here). HT Dave Tallon.

Photo by insung yoon on Unsplash

Links of the week

‘Most AI benchmarks test for maths, science, and law, but none measure creativity. So we're building the first benchmark that reflects how our world works’. This is an interesting (just launched) idea from my friends at Springboards.ai - an AI creativity benchmark

The new Gartner CMO survey reveals flatlining marketing budgets (at 7.7% of overall company revenue) but lots of efficiency-driving efforts through AI. Also this: ‘Twenty-two percent of CMOs said GenAI has enabled them to reduce their reliability on external agencies for creativity and strategy building’. HT Matthew Kershaw

A big old (and well-shared) study on using GenAI for essay writing has shown that cognitive debt (the impact of outsourcing our thinking) is real, with users that used GenAI in the task exhibiting the weakest neural connectivity patterns, poor recall of concepts, a reduced sense of ownership, and homogenised outputs. But the bright spark in the findings was that if participants had previously thought or written about the topic before and then used an LLM, ‘AI-supported re-engagement invoked high levels of cognitive integration, memory reactivation, and top-down control’. Fascinating, and again all kinds of implications for strategy, knowledge work and learning. As Jonathan Boymal put it: ‘As an educator, this points to the key role of pedagogy in ensuring that AI supports, rather than substitutes for, cognitive engagement.’

Another really thought provoking presentation from the prolific Zoe Scaman on the state of strategy. Zoe also had a good way of using AI tools in problem framing.

I liked Francois Grouiller’s ‘Think-Prompt-Think’ approach for integrating AI into strategy or consulting work in a way that can help expand your thinking but maintain clarity. Similarities here to the way that I use AI tools.

And finally…

I liked this view of writing: ‘Thoughts pile up. Writing sorts them out.’ HT Hidde Douna

Weeknotes

This week I’ve been on the road (or rather on trains) in Europe, running a three day session for a leadership team in Paris, and then doing some work with my Diageo client in Amsterdam (from where I’m sending this). Gosh I love travelling Europe - the ability to jump on a train and be in a completely different city and culture in just a couple of hours is such a privilege.

Thanks for subscribing to and reading Only Dead Fish. It means a lot. This newsletter is 100% free to read so if you liked this episode please do like, share and pass it on.

If you’d like more from me my blog is over here and my personal site is here, and do get in touch if you’d like me to give a talk to your team or talk about working together.

My favourite quote captures what I try to do every day, and it’s from renowned Creative Director Paul Arden: ‘Do not covet your ideas. Give away all you know, and more will come back to you’.

And remember - only dead fish go with the flow.

Neil. This is fantastically interesting and timely. And who knew Palinsky (sp) complex adaptive theory way ahead of time!